IT was, as the French say, "un coup de coeur" — something like love at first sight, but stronger — when Josephine Baker saw Château des Milandes above the Dordogne River in southwestern France.

IT was, as the French say, "un coup de coeur" — something like love at first sight, but stronger — when Josephine Baker saw Château des Milandes above the Dordogne River in southwestern France. It was 1937. She was the black waif from St. Louis who had taken Paris by storm and still reigned supreme, dancing to hot jazz in little more than sequins and feathers.

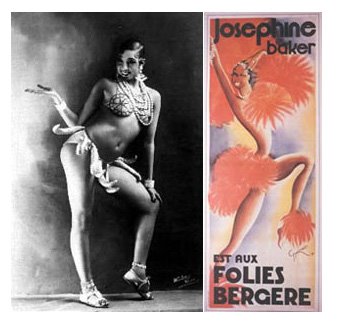

It was 1937. She was the black waif from St. Louis who had taken Paris by storm and still reigned supreme, dancing to hot jazz in little more than sequins and feathers.  Photographers snapped her picture when she strolled the Champs-Élysées with her pet cheetah, Chiquita; Jean Cocteau celebrated her in verse; mystery writer Georges Simenon fell in love with her; and Alice B. Toklas created a dessert called Custard Josephine Baker.

Photographers snapped her picture when she strolled the Champs-Élysées with her pet cheetah, Chiquita; Jean Cocteau celebrated her in verse; mystery writer Georges Simenon fell in love with her; and Alice B. Toklas created a dessert called Custard Josephine Baker.  Most Americans remember her only as the black Cinderella who left a racially segregated U.S. and found stardom and acceptance in France. But Baker was more than a Jazz Age siren, as visitors discover at the Château des Milandes, the fairy-tale castle where she lived from 1947 until the late '60s, raised 12 orphans and created a theme park dedicated to multiculturalism long before the term was coined.

Most Americans remember her only as the black Cinderella who left a racially segregated U.S. and found stardom and acceptance in France. But Baker was more than a Jazz Age siren, as visitors discover at the Château des Milandes, the fairy-tale castle where she lived from 1947 until the late '60s, raised 12 orphans and created a theme park dedicated to multiculturalism long before the term was coined.Baker, a civil-rights advocate who refused to perform in segregated American clubs, dreamed big. But she went broke trying to turn the château into a showplace for racial harmony and ultimately, she and what she called her "rainbow tribe" had to abandon it.

Privately owned thereafter, the château was purchased in 2001 by Henry and Claude de la Barre, who began restoring the 15th century castle and gardens. Now, the château is a museum dedicated to Baker, managed by the De la Barres' 30-year-old daughter, Angélique. The late Gothic/early Renaissance castle was built in 1489 by François de Caumont for his wife, Claude de Cardaillac. But like other embellishments, the medallions that honor him on the chimney of the small dining room were added by a later owner, Charles Claverie, who began a full-scale restoration in 1900. Thanks to him, the building was in relatively good repair in 1947, when Baker married band leader Jo Bouillon in the château's chapel and moved in. Baker added electricity, modern plumbing, a pool and tennis courts and decorated the guestrooms in the styles of different countries. The Art Deco bathrooms — one of which is tiled in the colors of an Arpège perfume bottle, the scent she preferred — reflect the taste of the Jazz Age diva.

Claude de la Barre and daughter Angélique found and reassembled much of the Baker-era furniture and memorabilia, including a stunning series of nude art photos of the star known as the black Venus.

Claude de la Barre and daughter Angélique found and reassembled much of the Baker-era furniture and memorabilia, including a stunning series of nude art photos of the star known as the black Venus. The grand salon, devoted to her music hall costumes, has a prize: Baker's risqué belt of gold bananas, worn with little else. Other displays tell stories about less well-known facets of her life, especially her work with the French Resistance during World War II. Before the fall of France, she performed for French soldiers; during the occupation, she is said to have passed important information about German troop movements, written on sheet music in invisible ink. In 1961, her adopted country awarded her the French Legion of Honor for her war efforts.

The grand salon, devoted to her music hall costumes, has a prize: Baker's risqué belt of gold bananas, worn with little else. Other displays tell stories about less well-known facets of her life, especially her work with the French Resistance during World War II. Before the fall of France, she performed for French soldiers; during the occupation, she is said to have passed important information about German troop movements, written on sheet music in invisible ink. In 1961, her adopted country awarded her the French Legion of Honor for her war efforts.Unable to have children of her own, Baker began adopting infants and assembling her rainbow tribe in 1954: first Akio from Korea, Teruya from Japan, Jari from Finland and Luis from Colombia, followed by eight more little ones from around the world. The nursery had a row of diminutive beds, and the children were raised speaking the languages and worshiping in the religions of the countries from which they came.

Akio Bouillon, who was at the château for the 100th anniversary of Baker's birth, told me that his mother cooked spaghetti for the family every Sunday night. "She was like a rock," he said. "For us, she seemed immortal."

In the kitchen, a 1969 photo of Baker in a bathrobe, shower cap and dark glasses recalls one of the saddest episodes in her life. Fundamentally impractical and profligate with money, she was deeply in debt by the late 1950s. Although Brigitte Bardot, Princess Grace of Monaco and many others tried to bail her out, she kept pouring money into the castle resort, with ever diminishing tourist receipts. The château was sold out from under her in 1968 to pay off creditors. Several months later, she broke into the property and camped on the kitchen steps in the pitiable state depicted in the photo.

Princess Grace ultimately found a new home in Monaco for the self-styled universal mother and her children, and Baker continued to perform, although her star was waning. She died of a cerebral hemorrhage in 1975 while launching a comeback in Paris.

Baker still has her fans. They come to the château to pay homage to an icon in a banana belt and find, instead, a stubbornly idealistic flesh-and-blood woman who wanted to believe that people could live together, regardless of race and religion. She may have lived in a castle, but the fairy tale ended, leaving her Cinderella again. (This article was written by Susan Spano, a writer for the Los Angeles Times).

No comments:

Post a Comment